This is going to be a long post, drawing on several disparate areas of experience and interest. Welcome to my mind…

Photographic Influence

Nice beech and hawthorn trees – shame they aren’t there any more

The Highlands are not like 18th-century Venice. On driving around – which you can do around here – the landscape is raw, rugged, elemental, positively harsh on a cold day. We do not sit around in powdered wigs playing the harpsichord of an evening.

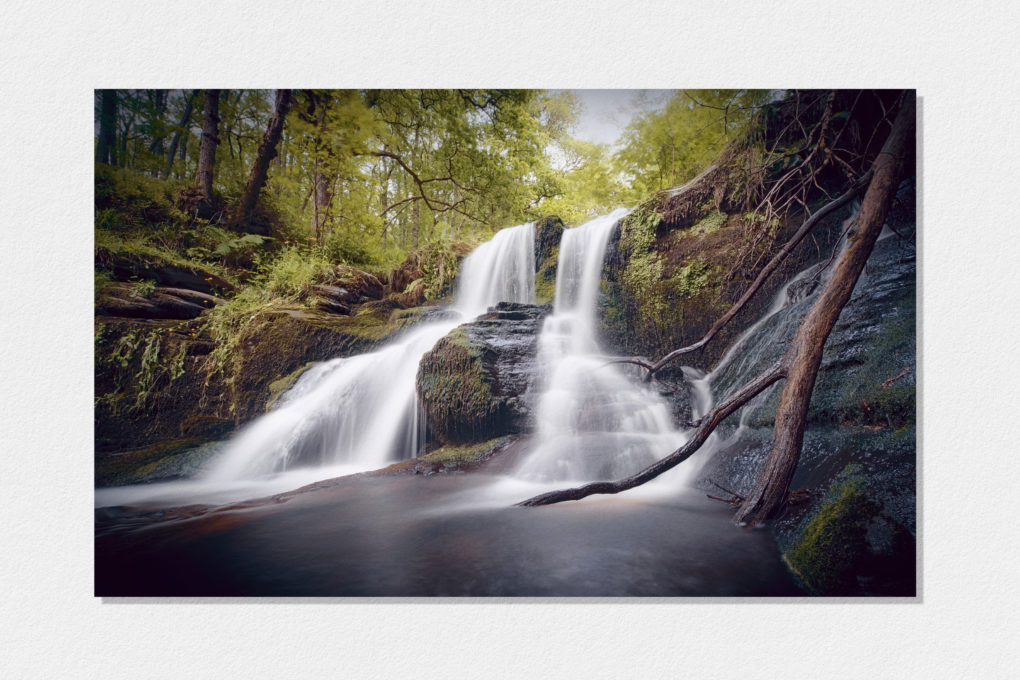

It is my opinion that landscape photography exists not to make merely aesthetically pleasant images, not even to convey a “feeling” from the photographer’s mind in the name of art, but rather to show and tell forth something of the landscape.

It is all too easy to go for a stroll, to get out into “nature” seeking photographs, to see only the shapes and forms of the land, hopefully cover it in contrasty dappled light; but if that is all that is seen in a photograph then it is the most absurd way to trivialize larger forces at work.

Worse still, it’s even easier to get into a mentality of visiting only known-good photo locations. “Saturday afternoon, Falls of Bruar” – nothing against the Falls, far from it, but it becomes a photographic rut devoid of sense of exploration.

I used to have a motto: “no landscape photos without saying something about the rocks you stand on”. It’s still a good thought, but even though the geology might date back 3.5 billion years, that is only one aspect of pertinent story, perhaps even the cheap and comforting option – looking straight to Old, bypassing the anthropocene; it reduces taking a principled stand to throwing out bland “statement”s or little stories and/or personal feelings, offensive in their inoffensiveness.

The PSNS Experience

A couple of months ago I attended a lecture at the Perthshire Society of Natural Science (PSNS), part of the “Curious Minds” series; the presenter worked for SEPA at Stirling University, and he spoke about Sustainability. Being brutally honest, it was not the most approachable of talks: a business person speaking from a mind of systems-thinking about corporate matters, with that peculiar management tendency to present a metaphorical briefcase of ideas supposed to be complete but leaving one wondering what nuance is missing – that’s not likely to engage the common individual who only wants to know how best to run their own house. I couldn’t help thinking of the only two occasions I’ve had any dealings with SEPA – first to ask how to dispose of film-processing chemicals and second for maps to avoid flood areas when buying a house; if SEPA are to offer the public a service, they have a PR hurdle to overcome…

However, I came away with the seeds of several thoughts that have since germinated.

The lecturer explained how SEPA sees companies on a spectrum from “climate criminals” (knowingly damaging the environment) through careless to compliant to champions. A lot of words containing “C” and “A” and a nice gradation from red to green, but that illustrates the systems-think.

More usefully, SEPA has expanded their remit so they now see Scotland from three points of view: there’s the environment which they still protect for its own sake; there’s social (concerning wellbeing when people go for a walk in the forests); and there’s an economic aspect.

Experiences of Farming

For lack of reason to the contrary, I’ve always kept an open mind opinion about livestock farming. As a confirmed carnivore, living somewhere between town and country, it’s not easy to see bucolic bliss as harm. However, in the past five years there have been three experiences that sounded warning bells.

First: in Galloway, I spent 7 months living in a run-down farmhouse in the middle of a livestock farm on a nondescript C road. If we left the gate open, sheep would come and mow the lawn and cows walk past the study window and fertilize said lawn on their travels. It’s all very well feeling close to “nature” when the sun shines, but when it rains and the slurry runs 4 inches deep corroding your boots whilst walking the dog, it is far from pleasant. It also “never snows in Galloway”, which doesn’t explain the 3′-deep snow that winter, requiring the farmer’s assistance to dig out the surrounding roads – which were made impassable by his own tractors bouncing along compacting the snow into undulating waves of ice in the first place.

Second: also in Galloway, when I spent 15 months living next to a different farm: there was a beautiful line of old beech and hawthorn trees running up a small hill, just round the corner from where we lived; the farmer chopped them all down to make way for root crops to feed his sheep.

Third: two years ago, I went for a walk along a glen and found a particularly pleasant viewpoint, a U-shaped glacial valley with corrie lochan and lonely pine tree in the basin.

The light and landscape that provoked further exploration

Seeking to revisit and explore further, I researched the area on Google Earth and figured, with a choice of two, the better track would be one running up the south/”left” side of the glen to reach further into the mountains. So a month ago I set forth, with young dog on a lead beside me, to explore.

About 300 yards from the carpark, we rounded a corner and saw a herd of Highland cows and calves. By chance, the farmer came by in his Landrover at exactly the same moment and said not to take my dog any further. Fair enough – answered my dithering wonderings on the matter pretty quickly – and the exchange was pleasant enough.

However, that does not explain why, having driven off ahead of me, he promptly shut and padlocked a 6-foot-tall gate across the path, leaving me and my dog on the wrong side with the cows.

Inconsiderate farmer shut this gate right across the path, blocking my escape with a young dog.

With no way through or around the gate, I had to persuade my dog to climb precariously over that ladder, knowing that if one paw slipped he could be seriously injured.

As for outdoor access code – “right to roam” – it would have been more considerate if they had erected some sign warning of impaired access nearer the carpark…

With three strikes against livestock-farming kind, it’s time to start formulating an opinion.

Connected Thinking

So after a bit of a delay we rejoin the walk along the glen, this time going down the right side of the river instead.

Realisation dawned.

The first realisation was that the view I had seen a couple of years previously relied on a trick of perspective – the grassland appears continuous over distance while actually the river lurks below the level.

As I reached the furthest point of my walk a few miles into the glen, turning back, I observed how the river had cut straight vertically down a metre or two, exposing dead tree roots in the bank.

Half-way back, I noticed dead trees all along the river bank, and just off to the side of the path I found a large expanse of land full of the bleached white remains of pine tree roots and it hit me that this was a peat bog – a genuine example of the kind of thing one reads about in “the Highlands”, as though that were some far-off place – well here we are, soil/mud/peat at our very feet.

Genuine peat bog, full of bleached white roots and remains of pine trees

And so I looked at it through SEPA’s eyes. Environment + Social + Economy <= Sustainability.

Following research, peat is deposited at a rate of about 1mm per year, so the 1.5-2m depth of peat beside the river corresponds to 1500-2000 years’ accumulation.

What we have here is not the wilderness beloved of landscape photographers, it is barren.

The interplay of light and shape and form of the landscape is utterly irrelevant while the natural pine trees that should be here lie dead in a large carbon sink, their place taken by monoculture fenced-off in enclosures for commercial gain. The parts of the glen that are not directly peat bog are bare through grazing of livestock whose methane and CO2 emissions are a major contributor to global warming. In the words of Henning Steinfeld, Chief of FAO’s Livestock Information and Policy Branch: “Livestock are one of the most significant contributors to today’s most serious environmental problems. Urgent action is required to remedy the situation“.

This is not wilderness, it is barren. It is not a wonder of nature, but artificial. It is not contributing to society’s welfare but its unsustainability harms the planet.

Sometimes, one has to remove the rose-tinted sunglasses and see how one glen encompasses in every aspect a microcosm of all kinds of problems. Just because it’s a sunny day does not make it a happy story.

What Next?

I’m still thinking about it. I’ve spent long enough wondering if certain environmental charities are “a bit hippy”, but the facts are irrefutable: that glen stands for the worst combination of (un)sustainability factors. Peat bog itself is a valuable ecosystem, but given the choice I would far rather have the pine trees back that belonged there in the first place. The idea of rewilding meets with favour. While I would not want to join or recommend any “-ism” (vegetarianism or veganism being defined in terms of negative ideologies), I am also in favour of taxing the supply of meat and other livestock products to better reflect the true costs, including environmental factors.